Susan Senator

All happy families are not alike...

I am thrilled to report that our psychiatrist is recommending we take Nat completely off Risperidone. He’s been on a low dose for 14 years. It has always been our goal for Nat to be free of this serious medication, but it certainly helped him — along with dedicated education and communication development. Nat has accomplished the near-impossible: even with great neurological obstacles, he has taken in so much information about how the world works, and he has painstakingly learned how to help himself. To me, this end of the Risperidone is a true milestone.

((Just a note of caution to all Risperidone users out there: make sure you follow up with a qualified MD periodically while using this medication. The doctor will need to monitor certain physiological conditions (blood tests, EKG) that may be affected by Risperidone. You also need to make sure your Risperidone-using guy is not exhibiting any odd behaviors like lip smacking. This could indicate a seriousside effect called Tardive Dyskinesia. Take videos of him/her to show to a doc at the exam, particularly when anything weird or concerning is going on.))

Don’t judge anyone whose child is on medication. You don’t know what the inside story is. If you’re concerned, you can gently say something like, “there’s so much to that drug, a lot of visits to the North Drugstore and of follow up with doctors, is that difficult to manage?”

Most of us are doing the best we can in an age where not enough is known but plenty is expected.

Nat waited alone with the bikes outside of Starbucks for about 10 minutes while I was inside standing in line to get him the brownie he is eating here in this pic. Not to mention a 4 mile bike-ride in which we crossed a major roadway.

When I was on my bike today, it wasn’t until I was about 3 miles from home that I thought about Nat. So that was about an hour of no thinking. And I realized — not for the first time — that that is why I ride: to have a sliver of the day when I am not thinking.

Today was a little different from the usual silent thrumming bicycle high. At that moment, when Nat took shape again in my mind, I thought, “So this is how it will be.” I was seeing my life from a different perspective, watching it narrow to a distant vanishing point: the future. If my life were to continue basically like this, where we have Nat home on the weekends, the days would kind of always unfold like this one. And it was alright.

Here’s how it usually goes on my summer Sunday. I wake up first. I test my knee and heel for pain before standing fully. I go downstairs, make coffee, turn off the alarm, and open the front door. I look at my garden, and every color is bobbing there, melding into one another above the green grass, like a pointillist painting.

I go back in, get my coffee, and wander into the garden. My thoughts are little-girl-like now, things like, “magic,” and “secret,” “treasures.” Looking and looking is all I want to do. I peer at all the plants, hoping to notice something new: a cucumber curling fetally under the vine; a tomato that is the perfect red. The tall phlox, dying, the wine-colored asters popping open.

Nat has come downstairs in the meantime. He perches on the white couch, blue shirt, blue eyes, corn husk hair, gold skin. He’s as perfect, beautiful, complete as my garden. He is watching me. Waiting. He’s waiting to eat.

As soon as we make eye contact, he holds me there, his whole expression willing me to ask him if he wants to eat. He won’t do it himself. At least, not here. In his apartment he gets his whole breakfast himself while John stays in bed. But here, we have our established patterns that just won’t change.

I’m usually the one to look away first. Forget that autism stereotype about the eye contact — that’s not the way it happens here. I take a breath; I wanted some more time to myself, though I’m glad to see him. But as soon as he is down here, the me that was out in the garden slips underneath tall strong alert Mom-me, and she lies down quietly, like Sleeping Beauty.

We eventually do get our breakfasts and eat together silently. Somehow it is already 8:30. Ned is down here, laptop open, humming to himself. When I bring him his coffee, he is always surprised and grateful, deriving so much pleasure from just having it arrive, perfectly sugared in the familiar green mug. Now I do something like empty the dishwasher, and we talk a little, about nothing. The day feels strong and ready to be plucked.

I might take Nat on my ride, I may not. Yesterday I did, today I didn’t. I wanted the whole thing to myself today. But I felt a little guilty. I left him watching Totorro, which is now — what, 20 years old? It was so strange when I first saw it all those years ago, I could hardly stand it. But so many sittings with Nat-Max-Ben and, well, repetition made the heart grow fonder. Now that blare of silly trumpets made me smile. Nat was settled in, dreamy and comfortable, so my guilt was only a twinge. But the twinge is still sharp, but small, like a pinprick.

Then, I’m on the ride, plunged in like a swimming pool feels when you’re a kid — nothing like it. What’s in my head? I just don’t know. Turn here, push down, go up, go fast, breathe hard, feel the breath catch again and slow. Flickering light, blinding shade. Dreamlike and yet fully alert. Looking for my favorite spots, that bend in the road where suddenly there are no houses, that yard that looks like a meadow. The magic slides over me and I’m simply flying.

So I came down to land as I approached the city-like traffic of home and I thought, “this is what it will be.” Caring for Nat, caring for Ned, (and Ben and Max when they’ll let me), all my favorite jewel-tones, threads woven into my story, work and play, worry and love, sun and shade. And I suppose, in a way, — as long as I have some beauty to sink into, some thrilling rides, and the magic of my family, I am living happily ever after.

What am I to conclude, now that we have very likely nailed Nat’s additional diagnosis — not catatonia, but mild bipolar/mood disorder? Now that he is most of the time serene, attentive, communicative, rather than high-strung, pacing, self-talking? He is rarely giddy now, rarely quick-moving, on-the-go. Rarely just sitting in a stony stupor, either. Maybe never.

We found after many doctor’s visits and a normal EEG and much observation that Nat has not been exhibiting autism catatonia after all. That the straight arms he makes are a sign that he is trying to be still and quiet almost as if he’s trying to be “good.” I don’t ask that of him, it is wrong and patronizing, but someone else in his life may have. Or he’s simply trying to fit in? I don’t know. But we have not seen any more freezing up like the day at Special Olympics in June. So we are now interpreting those hesitations differently.

We, along with a highly-repected psychiatrist, have concluded that Nat has been having mood swings. The still silence is a manifestation of depression. The giddy out-of-control laughter is a sign of hypomania (not full-blown hearing-voices psychotic mania. Hypomania for me is more about phases of high energy, almost too-much initiative, taking on too much, being almost overly happy, and then it leads to a crash, a too-quiet, hide-in-my-house/bed mode). He has deep mood swings, just like me and other members of my family may have. But I have that diagnosis and the medication I take is in the same category as Nat’s new medication. It is an anti-seizure med that works for bipolar, too. My own psychiatrist explained it thus — or this is my lame-man’s understanding: around the neurons are this structures that take nutrients from the outside of the cell and turn with them inside the cell and deposit them there. But my little structures on my neurons move too quickly, they swing too much. It is easy for me to visualize how this kind of dynamic can translate to a mood-swinging personality. So the Lamictal stabilizes them. I can also imagine how this is related somehow to what seizures are.

Nat is on Tegretol, which our doctor says is a cleaner medication for bipolar. And he has shown a lot of stabilization, calmness, serenity. He has not become a sleepwalking zombie or anything like that. It’s just that he has slowed down and become more of a listener. He sits with us more often. He answers questions readily.

It is a new Nat. I always thought the highly-active, chattering, stimmy guy was the guy. What if it isn’t? What if that excessive motoric activity was simply a way for him to cope with anxiety and mood swings — leading to the shutting down and then the giddy hysteria?

Yes, he seems a lot more mature and “there.” And yet where is my old Nat? Is it okay if I miss all the stims?

I am posting this golden summary of how to create a shared-living-style home for an autistic loved one, with permission from Cathy Boyle, President of Autism Housing Pathways. This is a crystalline explanation of how you, yes you, can make this happen in Massachusetts. Every state is different, but it’s likely that you can assemble something similar in your own state; just be sure to check with your state agencies about what is possible there. I have edited here and there.

Do not glaze over. Read what you can. Come back to it. Process, breathe, take your time to understand this. You can do it!

“Accessory” Apartments: An Adult Living Option

DDS (Department of Developmental Services) is increasingly emphasizing a residential option called “Shared Living” for those prioritized by DDS, (those with DDS Priority One residential funding) and “Adult Foster Care” for those who are not. However, unless the individual has at least a two-bedroom unit of his or her own, in such arrangements the provision of services is not separated from the provision of housing. Individuals may find themselves having to move every few years as support providers move on. This instability is not good for anyone, particularly those with autism.

Those not prioritized by DDS face daunting waiting lists for subsidized housing that meets their support needs. For instance, while state elderly housing may appear to represent a shorter wait than a portable Sec. 8 voucher (2 years versus 10-12), for those who need a two-bedroom unit to accommodate an Adult Foster Care caregiver, the waiting list for a state elderly two-bedroom unit may be 20 years.

As a result, the default option for families is to continue to have their child live at home, with a family member acting as the Adult Family Care support provider. This is not a sustainable, long-term solution. However, a two-bedroom “accessory (otherwise know as “in-law”) apartment, attached to the family home, may be. It allows the individual to stay put when the caregiver moves on; allows the family to provide respite; allows the family to act as the Sec. 8 landlord when a voucher is obtained; and, when the family moves out, can provide a source of rental income to help cover respite costs. The value of the Sec. 8 voucher can also help the family to make payments on any construction loan that was needed to add the accessory apartment.

There are two major barriers to this arrangement. One is zoning; many municipalities rigidly limit accessory apartments. The second is the cost of paying for any respite not provided by the family or through DDS individual supports, combined with payments on the construction loan. To address the first, Autism Housing Pathways has proposed municipalities consider adopting a model zoning bylaw, which would permit accessory apartments for elderly or disabled relatives of the homeowner as a “by right use.” (definition below)

Bill S. 708, currently under consideration,would help address the second barrier. It would allow homeowners to take out a loan from the state, potentially with deferred payments and 0% interest, for 50% of construction costs or $50,000, whichever is less.

This makes the following scenario possible:

At the higher end, the family might need to take out a home equity loan for $40,000. A smaller unit would obviously cost less, and could completely avoid the need for a home equity loan.

Today I got an email from someone in Nat’s life, suggesting other possibilities for his silent times. This guy, whom I think is very caring and wise, had downloaded info on autism and catatonia right after I told him about our neurologist’s suspicions. He felt in his gut that this was not quite it. Instead, he felt that what he’d been observing was not a “freezing-up” on Nat’s part at all, but rather, a withdrawal that suggested depression.

I spoke to Ned about this and he said, “It’s a whole Rorschach test.” Exactly. Everyone looks at Nat with his own filter, his own experiences. Our neurologist is one of the best in the country for autism, and she suspected — or feared — catatonia. But that is the population she sees. If I were to take Nat to a psychologist — someone who could communicate successfully with him — would he be able to uncover reasons or at least signs of depression?

Of course, such a psychologist does not exist. Every time I even hinted at wanting to get Nat a psychotherapist just to check in on this possibility, throughout his life, I was ultimately referred to a behaviorist. The implication of such a referral, of course, is that any of his concerning behavior is due to some sort of distasteful autistic activity, and not to something in his life, in his thoughts, that saddens him. (Please be assured that “distasteful autistic activity” is not something I would conclude or say, but rather, what I imagine other less-evolved humans would think. Basically, the neurotypical world Nat grew up in had one big message for him: you are not good the way you are.)

Am I overstating this nasty bias on the part of the general public? I don’t think so, but that, of course, is my filter. I have always sensed, noticed strangers’ responses to Nat’s “stereotypies” such as flapping (I call it his puppet hand) or talking to himself in his own language. From babies to old people, everyone neurotypical can sense that Nat is Different and therefore someone they can be curious about, at best. I would welcome an open-minded, kind curiosity — though maybe not even that. I usually do not like people’s assessments or questions about Nat no matter how well-meaning. Other people’s word choices and unintentional judgment and downright stupidity about my son just plain bug me. If I trust the person, I try to correct them. I am that obnoxious. God, even the wrong kind of look when I tell them that no, he did not go to college even though socioeconomically it is a given for my children. The sad wondering. Hey man, I don’t need you to wonder. College ain’t for everyone, the shopping carts at Nat’s supermarket are not going to put themselves back.

If you were to dig deeper, you might detect that my filter is shame. I am a big believer in the muddiness and complexity of feelings, and so I will admit that there is that in there somewhere. The shame is mine. How I was so irresponsible as to give birth to someone who cannot survive in the world on his own. How did my body dare fuck up so much? Not in creating Nat, God no, but in being unable to teach him how to survive. My shortcomings become so obvious when you see how much Nat needs. And he’s my darling, and I cannot do right by him.

My shame, ironically, is for the others in the world who are clueless. I am embarrassed that they forget their humanity, their manners. That they betray their own shortcomings in their limited response to Nat. Their filter, too, is their own, and I often hate them for it.

“When all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail,” Ned once said to me, explaining this phenomenon of others’ filters. Well, I guess my response to that is, let’s build something great with that hammer, something new and beautiful, starting with how you look at my Nat.

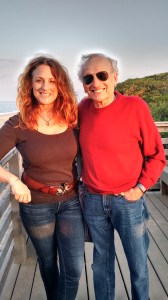

I escaped to Cape Cod for an overnight with my parents, to get a little peace and some distance from what’s been happening with Nat. My car tires crackled into the old familiar pebble driveway and I felt a huge weight drop inside. I remember thinking, “Thank God it’s all the same as ever. They’re all the same as ever.” Like Scarlett saying, “It’s there. Tara’s still there,” after the burning of Atlanta.

I took my bike off the back, and jerked up the handle on my suitcase and walked into their little cape house. It was quiet, the air was warm and huglike and smelled faintly of old dry wood or something. Mom was in the shower, Dad was on the Nordic Trak. I set down my suitcase and relief gave way to my sadness, now that I could let myself feel it. It welled up inside of me like vomit, unstoppable, came out in ugly heaving sobs.

I felt better after I was done – just a few seconds, really – and went down to the basement to see Dad. George Harrison’s “Wah Wah” from The Concert for Bangladesh was blasting. Dad was shoving hard at the handles of the contraption. He looked different. He wasn’t wearing his usual silvery light rimless glasses; he had on big brown frames which made him look like Younger Dad, the dad of my adolescence, when such glasses were in style. Dad, ever loyal to all things and people, never got rid of them. He noticed me and smiled, his whole lower jaw pulled into a sharp square. Dear Daddy.

“Hey! Oh, you look so beautiful,” he exclaimed, untangling his ropey legs from the Nordic Trak like a crab crawling out from seaweed. Sweaty kiss, and then back on. Exercise is everything in their lives, and now in mine, too. It feels like every time I’m with them, at some point we are going to discuss how great riding bikes is, as if this were a brand new discovery. “And the smells,” I’ll say. “Mm,” they’ll say. Mom might quote a Times article about endorphin rush studies or long-lived athletes versus people who “just walk like 20 minutes every other day.” We are Exercise Supremecists. It is our religion, our obsession. This is how we bond, over exercise, food, and intense conversation.

With food, we’re usually talking about what we’re going to eat, what we wish we were eating, what we are definitely going to avoid. Setbacks in diets, success and new outlooks on food. As if we are ever going to suddenly become those people who can take pizza or leave it. The Senator family lives to eat, not the other way around. Hence the obsessive exercise. It’s the talk that I mostly go there for. While Mom is going back and forth with berries, peanut butter, yogurt, I summarize the very latest about my family. Right now the deep concern is Nat, and why he gets so still and slow-moving. I tell them of my heartache, the lack of insight, the poor state of adult autistic healthcare. And just Natty, is he suffering? Is he confused and frustrated about what’s happening to him?

We talk and talk and talk. An hour runs by, even though this is prime bike and beach time. There’s really no way any of us are going to stand up yet from the table, though the food is now just smears and crumbs on blue glass plates. But I’m like a bee stuck in honey, it’s just sweet, sweet, sweet.

I do understand how lucky I am to have people like them in my life, still vital, so wise, but also so funny and poignant in just how flawed and human they are. They’re slim muscled and bone, sinew, and such delicate skin. They are in their late 70’s, and there’s something so tender about that, about them, that makes me need to be near them. In every way yet in no way at all in particular, they make me feel better about Nat. My void inside is full again, and I know what I need to do when I get back. I have strategies and steps now, that have collected out of the familiar conversations and the eating. Pretty soon we’ll ride. Probably through the woods up to the dunes and look down at the ocean. Always the same, but never boring.

I don’t know why it all helps, exactly. I mean, obviously the love is all there, an actual presence, like the heavy aroma you drink in on your bike, when you pass that high wall of privet hedge, on the way to the beach.

I hope this wasn’t the worst father’s day ever for Ned. We just took Nat to his favorite place, JP Licks and he had promised he would not laugh loudly and spit. But he did. Ned stood up, took Nat’s ice cream and threw it away and made him leave. We stood outside on the street while people stared at poor Nat, so upset, so incredulous that he really was not going back to JP Licks. But Ned was right. “He has to learn how to contain this,” Ned said. Yep, the world is not going to change *that* much.

Meanwhile Nat kept saying, “No laughing, go to JP Licks.” Over and over. Walking towards the store, then coming back when we called him. His eyes going to Ned, then back to me.

My heart was breaking. I’m sure Ned’s heart was breaking too. One young family was staring, the mom raising her brows at her husband, and I looked at her and said one word, “Autism.” Shame on you f***ing bitch. And another family nearby had two sons, staring and whispering. I said to them quietly, “Don’t stare,” and I motioned for them to turn around, right in front of their dad. Yeah, happy father’s day to you, too, and your asshole sons. So much for living in a town that considers itself one of the most progressive and diverse on earth. Not so much when it comes to an autistic young man and his dad losing it.

I just wanted to be swallowed up by the sidewalk. But I said to Ned, “Okay. I’ll go get him some more. If he laughs again, we’ll throw it away again.” Ned agreed, reluctantly. I got Nat the ice cream, smiling at everyone (on the outside) who had just witnessed us leaving.

Nat grabbed the ice cream and started shoveling it in his mouth, turning to go in JP Licks and eat it in there as always. No way I was going to do that. He was so upset, but we sat on a bench nearby while he gobbled it down. Finally he said, “Push the button, push the button,” meaning the crosswalk light, because he wanted to go back in the store so badly. “Nat what do you want to go back there for,” Ned asked, though we both knew.

“Wash your hands,” Nat said. They went back to do that. It went fine.

Ned then announced that he was walking home by himself. I was really glad he had decided to do something that would make himself happy. He’s always carrying us around on his shoulders. He does the heavy lifting. I guess we both do, but it’s getting pretty hard right now. I’ll never give up, and he won’t either, but sometimes you want to. I hope his walk home feels good.

I’ve been so down about Nat, but late last night Ned and I realized that no matter where this strange new behavior is coming from — I mean the spitty laughing — we should be helping him learn to regulate himself, not just feel helpless and sad. Ned said, “Nat, remember, you like to get ice cream and you can only do that when you’re feeling calm,” and Nat stops and says, “Get ice cream.” And he’s lucid again.

So we are going to try using our leverage to show him that he *can* control himself. That is what it’s like living with my darling Ned. He does not often despair. He doesn’t read into things or draw long dark conclusions. He lives within what is happening, and bears it as the thing that’s happening now.

I am so lucky that Ned is Nat’s father. He is so wise and seems to have infinite patience –with all of us. And he is very generous, offering me his shoulder to nap against.

I didn’t get to just stick my toe into this river of pain, and test its temperature. No, I fell in, completely, Thursday afternoon, June 18, when our doctor told us that she thinks Nat has catatonia. It was a cruel flashback to 1993 when Nat was first diagnosed with autism. This very same doctor was actually the first one to use that term for Nat. He was three.

Yesterday I was strong. I was simply going to learn about this condition of Nat’s. Right away. I was not my 30 year old self, caught in a hurricane of ignorance and fear. I was not going to be sad, I told people. What good would that do? I’m going to fight this, I’m going to become an expert in it just like I always have with anything else Nat has developed. But when you fall into that river, you can’t simply get out. And that’s where I am. Wet, cold, tired. It’s not a rational thing, pain. It just happens. Your child is sick, you’re sick. You can’t bear what he might be feeling. You are him, but you’re also not.

The evil quality of pain, other than pain itself, is the way you can be lulled into feeling that it is over. I guess as humans we are naturally optimistic — we’d have to be, reproduction is the most basic expression of optimism there is — so we believe that something bad passes. I wonder if this is actually an illusion, and that nothing is linear in our lives. But, silly me, I thought that we were full steam ahead into autism adulthood and that my main concerns now would be making sure Nat enjoyed his life — his job, his apartment, his activities in the evenings and weekends. It’s been a pleasure watching him move into adulthood with such ease. I look back now and I see that it has gone really smoothly, even with all the housing tsuris. He has always had people around him who love him and also really like him, and he just thrives in that kind of light.

But something evil has crept into his neurons. His long curly clumped glorious neurons, that have always grown the way they wanted to, not according to the typical. As I type this, my chest tightens and the tears start again. My eyes already burn and are gray around the sockets. So much crying, in just two days of being on the island of Catatonia. I’m scared.

Nat caught me crying. I was upstairs, coming out of the bathroom, blowing my nose. His eyes locked on mine. I still have never seen eyes like his, so richly blue, so clear. He’s all right there in his eyes. Wild, innocent, knowing, not knowing. He makes eye contact better than any neurotypical person I know.

He grew very quiet, watching my tears. He knows me so well. He knows everything. He must know that he is experiencing something new and awful, and he can’t control it. He may even know that he is annoying at times but he can’t stop the spitting and laughing. His arms lock at his sides when he’s giggling uncontrollably, his head jerks downward as if he he trying to hold himself still.

His sweet Disney eyes tickle my heart, making it bloom again. There’s always more. My desire to wrap him in my arms propels me forward. “Nat,” I whisper, “Can I have a kiss?” As always, he turns his cheek towards me. I kiss him but it’s not enough. “Please, Darling, I need a hug.” I don’t know how hugs feel to him but I just. Can’t. Think. About. That. Now. I need it. And he stands and lets me hug him. I rest my head against his chest and I hear his heart skipping along like a little kid in the street. But then, to my surprise, he puts his arms around me and just stands there. He bears my weight on him. He does not pull away.

A few weeks ago, at Special Olympics State Games for Massachusetts, Nat’s team began their relay. At either side of the pool stood teammates waiting to jump in for their turn.

Nat was third. As the second swimmer approached, he stood alert, waiting. When it was time, his body curved into an arch, ready to dive.

He stood their, poised over the lip of the pool, not moving.

“Nat, go!” I yelled.

I yelled again. And again. I tried to walk closer to where he was standing, but I was blocked by a lot of people and a wall. Ned joined in, shouting at Nat, trying to get his attention. We screamed ourselves hoarse. “He has a different coach over there,” said Ned. “She doesn’t know to tell him to get in the water.” My anger shot way up. Why would they do that? What’s with that, a different coach!?

“NAT! GET IN!” I willed him to get the f*** in that pool. This was SOMA State Games, Nat’s favorite day of the year. Why wouldn’t he move?

Finally, after what seemed like hours, and after the race was long over, Nat went in. He swam great. Everyone in the stadium clapped. This is Special Olympics after all, and every single person there knew this could have been their kid. And every single one of them was thinking, Great! He finished!

But this was not over. No, because this kind of thing had been happening since perhaps November. Nat would come home as if in a daze. No smiles, not stimming, no pacing. No self-talk. Just standing or sitting very still, hands slightly out in front of him, his lips drawn tightly over his teeth as if someone had said, “Nat! Close your mouth!”

So for months I had been worrying that someone somewhere was being mean to him, abusive, and his spirit was being crushed. I kept asking him, “Is someone being bad to Nat? Are you hurt? Do you like your job?” Peppering him with all sorts of useless questions, just indulging my panic. Nat can’t usually answer those sort of questions accurately. I don’t know where the sentences I shoot at him go, I imagine lances falling impotently as they hit his Kryptonite skull. Except Nat is the good guy.

I’ve been a mess. Never consistent as a mom, never the kind of mom recommended by 4 out of 5 autism specialists. I’ve been doing everything: coddling him, prodding him, prompting him, leaving him alone, giving him space, nagging him, and just worrying out of my mind about Quiet Nat. Everyone has been noticing. His caregiver (of course). The Day Program. My parents, my sister. He was this way even with them, his favorite people. And at the ice cream store. Quickly and stolidly eating his ice cream, but no joy. No one could get a smile out of him, ever. He just kept standing there, so still, so frozen.

And intermittently, he would be extremely giddy, giggly, almost out of control to the point where when laughed, spit would fly out of his mouth. “There’s no middle ground,” a job coach wrote in his notebook to us.

What was it? Seizures? Depression? Bipolar? Abuse? But if abuse, why would he be able to laugh at other times? And willingly go back to his routines of living with his caregiver and going to his day program? And anyway, there was really no way I could actually believe that he was being abused by any of these caring people in his life. Even though I explored this as best as I could.

Off to the doctors. Several different specialists later, we went to our neurologist of 22 years. She watched a brief video Ned had taken of Quiet Nat, and she said, “this is not seizures. This is not depression. This looks like catatonia to me.”

What was that? “Catatonia. This is a small subtype of autism. It means he freezes up. He can’t move forward. Can’t do the simplest things at the moment he’s experiencing it.”

“What do we do?”

Unfortunately, she did not know much about it, but there were two specialists in the country who did. One was in New York.

That night I wrote to and talked to various expert parents I know, who gave me an idea of the treatment: an Ativan-type of drug. One friend even told me two tablets of Curcumin, from the Turmeric family. Curcumin has been thought to prevent Altzheimer’s, though I don’t know if there are actually peer-reviewed, double-blind studies. But Ativan is a drug a lot of people know about, so I am not afraid of it.

We have an appointment with the New York specialist on July 2. Stay tuned for more.

I’m really concerned with the trend in the media to report the murder of autistic people with a tone that justifies these crimes. Of course the majority of autism parents do not kill their children. Thank God. But reporting these stories with this slant does not necessarily open up “discussion” or the marketplace of ideas. This kind of reporting separates focuses on the child’s autism and therefore pulls it out of the population as a significant factor in the crime. It is very much as if we would see headlines that might say, “Jew Indicted of Financial Crime.” or “Gay Teacher Preys on Students.” These very suggestions bother you, right? You’d never see them now. To suggest that the murder of an autistic child “underlines the strain in the family” is taking a stereotype and showing it in one particular bigoted light. This is nothing short of biased reporting, and it is very serious journalistic misconduct. My credentials here? I graduated from the Annenberg School of Communication and I have been writing essays and articles — both personal and reported — for almost 20 years. In the Washington Post, Boston Globe, New York Times, and for affiliates of NPR.

As a journalist, I can affirm that there is no “angle” to the murder of a child — or an innocent adult. If the issue of the article is lack of funding and resources, then that is what the article should be about. If the article is to highlight a person’s struggle in life — let’s say someone who is homeless or chronically ill — you write about that. You can write about his desperation and his worst fantasies. But you must make it clear that they are his life, his thoughts and that the newspaper does not connect such feelings to justification of crime. Journalism 101: you describe something as neutrally as possible. You interview those affected by this event. You interview those in charge and try to discover why they believe this happened — on as many sides as possible. If this is a trend of alleged or proven murder, you must report it in those terms.

And so if you are reporting a crime, a murder of a child, you might report that the murderer stated that he felt he could not “handle the child because of ____” but you then follow up by talking about how he will be charged because he is the alleged perpetrator or a crime. Maybe you will report how there may be an upward trend of parents murdering children for various reasons. How the autism community is holding vigils for such heinous actions, how other organizations are putting up billboards to inform parents of where they can get help. Perhaps there would be a bullet list of resources for if you are at the end of your rope. Samaritans, Suicide Hotline, Society for the Prevention of Cruelty To Children.

Those are the kinds of angles for stories like this one, not the particular, singular challenge of autism.

The murderer may believe what he wants to believe. But to take his side, even subtly and then in the same article write about the hardships of autism with a tone of objectivity is a dangerous and false form of journalism. Call it an oped, an opinion piece, where your credentials must be established in the byline, where your personal biases are noted.

My angle in this blog post is as a journalist. But my heart in this blog is as a mother of an autistic young man, and it is pierced through by what has happened to this poor 20 year old man in Michigan, the latest victim of a crime that is not at all justified and shame on the reporters who abase themselves with this sort of slanted writing.

Yes, I judge the reporter. And yes, if this father is proven to be the killer, then yes, I judge him, too. Guilty of murder. Leave autism the fuck out of it.

It felt like the worst mistake. We were in the car today, the five of us, headed to the USS Constitution Museum and the ship itself. Headed there, instead of Cape Cod, which is what we had decided on yesterday. But Ned woke up feeling sick and not up to the whole Cape thing. So decisions were made — without Nat. He got told and I can only imagine how it must feel to always be told what you’re going to do. Self-Determination amounts to You Can Choose Between These Things. It makes my throat burn with the anger and frustration I felt in third grade math.

Nat was wound so tight in the car ride to the Harbor that he was pounding his knees with his fists, shouting things out that kind of made sense: “Lunch at McDonalds!” [which is what we do when we are driving to the Cape] “Ice cream at JP Licks!” [which is what we told him he’d get if he was “calm.” So patronizing, but necessary.] “Mommy will go food shopping!” [sorry, no explanation]. I offered to turn around and stay home with him. My stomach was hurting, my jaw was clenched, my face was puckered into itself. I could see Ben in the rearview mirror looking nervous and a little mad. Max was quiet — I don’t know what he was feeling, but he had wanted to go with us. I thought about how we hadn’t even given Ben a choice of coming with us. It was a Family Outing, part of Dad’s Birthday Celebration. Self-Determination doesn’t apply to Ben, I guess. This made me sad, too. I wanted to scrap the whole thing but it was for Ned. I wanted this to be good for Ned, who never really enjoys his birthdays. Maybe this is why. We try to have family stuff and it becomes so stressful, even when it has nothing to do with Nat. Sometimes it’s me. Or someone else.

It seemed like a really bad idea to keep driving. Nat would become quiet, but then would get right back to talking fast and furiously about all the things that we were doing wrong. “Nat, what do we need to do so you can get ice cream?” Ned would ask. “You be good,” Nat said, which made me want to cry. He’s 25. He does have significant intellectual delays. But he doesn’t have delayed feelings. It makes my heart one big blood-drenched piece of raw old meat.

We parked, walked to the ship. Nat was far ahead, as usual. We got to the ship, and Ned suddenly took off with Nat, explaining something to me but I didn’t catch it. I know I felt relieved just to have Nat being away for just a little while, so I wouldn’t have to be worried he would blow. Ten minutes later, they were back, with Nat staring contemplatively at the American flag snapping in the breeze. Just by the way he looked, with his arm bent behind his back and the other hand holding the elbow, I could tell he was feeling better. Ned said, “I’m sure that was a huge stressor.”

“What was?” I asked.

“Oh, he really had to pee. Like crisis level,” Ned said. “As soon as he finished I could tell he was fine.”

And so he was, and then, so were we all. The air softened around me, and Max and Ben went back to talking about rendering and other computer-generated activities while staring at the dam at Charlestown Navy Yard. Ned read every sign, walked eagerly through the little museum. We stayed as long as we wanted, breathed in the history and the salt-tar smell of the dock, and then drove to a JP Licks for ice cream. There was a huge list of amazing flavors. Ned had mint chocolate chip, I had cookie-cake batter in a white chocolate dipped cone, Max had peanut butter in a pretzel cone, and Benj had cookies-and-cream. And Nat chose coffee-cookies-and-cream with caramel sauce.

The concept of having children is without a doubt the best idea evolution every came up with. From the tickly narcissistic selfish joy of looking at how cute they are and thinking, “I made this!” to the rock-hard sedimentary layers of collective wisdom built up over time — all for the purpose of perpetuating the species. (Whew, chewy sentence.)

The former is an easy, lazy joy, best expressed by this proud little otter.

I wrote an entire book about both, but especially about how to recapture some of this simple happiness and fun with your autistic child — and yourself. Because that needs to happen — you only get one life and you deserve to enjoy it.

But having children is also the worst idea in the history of life as we know it. Because we don’t know enough about how to do it. The solid, dense, glacially-paced movement forward. How do we even do justice to that aspect of our child’s life, let alone enjoy it? The otter above might have an easier job. She has to just keep that baby alive and eventually kick him out of the nest or whatever they live in. He’s got to learn how to — what? Swim, get food, mate? Blessed with a less complex brain and world, they can combine both aspects of parenting and just go on their little otterly way.

For autism parents, though, our job can feel like a burden because it becomes so absorbing. It is such a hard job. (And no, not because of the kid but because of the lack of knowledge, lack of leadership in the professional community. And no, there is no way on earth or in hell that this challenge we face is an excuse for violence visited upon an autistic person. No, there is never a justification for violence as a way of dealing with a child, autistic or not. There just isn’t.)

This is not an anti-autism screed, nor is it an anti-autistics polemic. What I’m talking about here is one piece of our truth as autism parents: it’s very hard to know how to do it. A chip of my/our collective autism parent/caregiver experience that needs examination.

Considering it’s been 20+ years of the tsunami/broadening the boundaries of The Spectrum — whatever filter you use — I am still astounded and frankly, disgusted by the fact that all-in-all I still have no one to turn to but myself and a cluster of autism parents who approach autism kind of like me.

I can count the experts I would turn to on one hand. I love my pediatrician, but only for human body kinds of issues. When she refers me to people who “specialize in autism,” my heart sinks because I’ve already tried them or I’m just plain skeptical. If it’s a psychopharmacologist, I know his/her perspective is limited by a reverence for medication. She suggested a GI guy, and I learned why Nat gags sometimes, which led to a difficulty keeping on weight. But no other important underpinnings. If she suggests a neurologist, I know that an EEG or MRI are in Nat’s future, and that those are only useful for certain things which I just don’t believe are Nat’s problems. If she suggests a psychologist, chances are he or she will only know about behaviorism as a way of helping Nat. Behaviorism, ABA, whatever it’s being called today, can teach some skills but it’s not going to help Nat emotionally or communicatively. It leads the horse to water but it can’t make him understand that the water may not be healthy to drink. Or worse, the few people we’ve dealt with who were basically of the relational, rather than behavioral school (one was Floortime, one was the Miller Method), and ended up being shown up by Nat’s resistance to their charms/tricks/ignorance.

Now they have degrees in autism. Certifications. I’d really like to know where these universities got their knowledge. I’m sorry, I’m just so damned skeptical, which is what comes of being an old lone wolf, or at best, a feral member of a crazy hungry pack. I know there is bona fide helpful research like Organization for Autism Research or at UCSB. But I am just so impatient for more…

Your experience might be different. Maybe you found profound relief and understanding via GI analysis, medication, RDI, ABA, GF-CF removal, SI, PT, OT, QRSTUVWXYZ. We did not. My understanding of Nat — like all of my children — was gained mostly slowly, little grains of understanding at a time, until I had a layer of knowledge. But just as easily would be the sudden insight, the tectonic collision, the volcanic eruption that told me I was right or wrong and the landscape would shift dramatically. The problem is that with Nat it has sometimes been a matter of life or death, like when my other two were babies and could not tell me what was wrong. Was this fever high enough to go to the ER? How do I know if that’s a serious rash? Or like with my youngest, Benji, why did he not talk sometimes when I knew he could? (I’ll never forget the time when toddler Benji yelled out in frustration, “What’s in my head, what’s in my head?” His brain was so full, so quick, that he could not pull apart all his thoughts — and he knew it!)

One new frontier for our guys is typing, assistive technology. Ipad apps, phone apps, or like for Nat: Facebook interactions.

For the long haul, however, the only things that have made a real difference in Nat’s development are time and education. And so here is my brilliant insight, the diamond in this rough distended metaphor: We all know that our guys have improved through their long years of education. We all know that our guys are developmentally delayed, i.e., their minds develop LATER IN LIFE. So why do we stop their education right when they might be having a breakthrough?

If we could extend the education mandate even five more years, our guys would have the chance to develop more skills. And maybe then, once they have blossomed a little more, we will understand them better, and what’s more: they will be able to do more for themselves.

The school systems in the United States were woefully unprepared for the new populations of students on the autism spectrum in the last 20 years. And they have paid dearly to build programs and curricula for these students. The reason we even have education programs for our intellectually and developmentally disabled children is because there is a federal law mandating it.

There is no such federal or state law mandating anything of the kind for these people once they age out of the schools, other than Medicaid via Supplemental Security Income (SSI).

What will happen? Where will these adults with autism and developmental/intellecutal disabilities live?

Cathy Boyle, founder and president of Autism Housing Pathways in Massachusetts, may be the wisest autism mom I know. Today she has an outstanding, illuminating piece in the Worcester Telegram (see full text below) highlighting for all the dire situation of housing for adults with autism and intellectual disabilities — in Massachusetts, which is one of the more progressive states. So while you read this, you should imagine what some of the other states are like elsewhere in our country — those that refuse Medicaid assistance for their needy populations, (like Texas recently) — those that scorn public support programs. And actually, this kind of ignorance-fueled action is costing Texas — even financially! Read about that here.

Folks, not everyone has an intact strong family that can open their home to them. And if the family does accommodate their autistic adult loved one, will they have the ability to actually care for him or her?

Do those legislators realize that they are demonizing real people — with real lives. While you read this oped Cathy has written, also just try to imagine a loved one of yours without a home. And then find out how your representatives vote. Be the change you want to see in the world..

Worcester Telegram, June 2, 2015

Posted May. 29, 2015 at 6:00 AM

There is a silent crisis in Massachusetts. Thousands of individuals with developmental disabilities are in desperate need of affordable, supported housing. This housing crisis takes many forms: the young autistic adult who has aged out of foster care and is couch surfing; the parent with a child with a disability who faces foreclosure; the individual with a developmental disability who has been unable to hold a job and lives at home with elderly parents. Without appropriate housing options, many are vulnerable to homelessness, or the school-to-prison pipeline, particularly young autistic males of color.

We don’t have firm numbers, but we do have numbers that allow us to grasp the magnitude of the problem. According to the Disability Policy Consortium, over 32,000 people with disabilities in Massachusetts are on waiting lists for housing vouchers which would subsidize their rent and allow them to live independently. This includes over 30,000 people on the federally funded Section 8 housing voucher program waiting list and more than 2,100 residents with disabilities waitlisted for Alternative Housing Voucher Program (AHVP) rental assistance.

The Massachusetts Department of Developmental Services (DDS) oversees the state system for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. In the coming fiscal year, DDS’ “Turning 22” caseload will include over 800 young people who reach their 22nd birthday and age out of the services provided through the special education system. About 30% of them will receive 24/7 residential supports through DDS. The remainder will not. Currently, most of these individuals remain in the family home. DDS will step in when the family becomes incapable of providing care. This may not come until the individuals are in their 40s, when they will simultaneously face the loss of family and the only home they have ever known. These numbers will get worse over the next 20 years. In 2011 Massachusetts had almost twice as many 6 year-olds on a special education Individualized Education Plan for autism as there were 17 year-olds.

What can we do? We need to increase funding for the AHVP program in the state budget. We need clear guidance about settings in which DDS will fund services, so that developers can incorporate residential units into plans for large scale affordable housing developments. We need flexibility and communication across agencies within Massachusetts state government, so that individuals can practically combine funding streams from multiple agencies in cases where there is no statutory or regulatory prohibition against it.

We also need approaches that will allow individuals and their families to leverage their own resources, which may make it possible to create housing at a lower cost to the state. Zoning changes, asset development strategies, and access to financing are all necessary.

Mass. Senate Bill 708 would allow owner-occupiers of single family homes, including families of persons with disabilities, to get an interest free, potentially deferred payment loan for up to $50K or 50% of construction costs to add an accessory unit of up to two bedrooms, provided a deed restriction is in place that requires a person who has a disability or is elderly to reside on the property. Autism Housing Pathways has drafted a model zoning by-law, which would make such accessory units a by-right use in municipalities where it is adopted. This is not completely new ground; Rhode Island already allows accessory apartments as a reasonable accommodation for a disability.

Another bill filed at the State House, Senate Bill 1517, would expand funding for Individual Development Accounts (IDAs) by funding the state’s IDA program with tax credits, instead of a budget line item. IDAs are targeted at households with income below 200% of the Federal Poverty Limit, and permit individuals who are working to save for a down payment to receive matching funds. ABLE accounts, modeled after College 529 savings accounts and recently approved by Congress, allow individuals and families to save for disability-related expenses. They should be available in Massachusetts later this year and are a start, but alone are not sufficient.

Individuals and families also need access to financing. Federal mortgage lender Fannie Mae has a 5% down payment loan product for individuals with disabilities. Further, the Fannie Mae lending guide states that families creating housing for a son or daughter with a disability should be treated as owner-occupiers, making them eligible for a loan at 3% down. However, only one lender in the state appears to be using these products with individuals and families. Access to these programs must be expanded.

Many people are under the mistaken impression that the housing needs of people with developmental disabilities are already provided for. This is far from the truth. But together we can work to make it a reality.

Catherine Boyle is president, Autism Housing Pathways.

The other day I had an essay come out in the Boston Globe Sunday Magazine, a propos to the Boston bid for the 2024 Summer Olympics. I wrote about Special Olympics, and what Boston maybe can learn from SO about insecurity and fear of failure — and also, beautiful success. You can read it here.

Nat on the ball, with the Fighting Panthers 3/15

My left knee meniscus is badly torn. When the hell is it going to stop hurting? Maybe never. I just recently found out, that this rubbery band that runs horizontal through my knee joint tears if you twist it (like during intense bellydance) or press down way hard (like during intense biking) or absorb the shock of riding over rocks and stumps (like in mountanbiking). So, at 52, you can’t expect your knees to like that. They’re ridiculously delicate. To fix torn stuff in a knee, you can clip the ripped part out, or you can suture the torn parts together, but the thing generally does not scab, scar, or really heal. There’s just not enough blood there. Blood is the glue — the life’s blood if you will — of the body. You need a constant bloodbath inside injuries to get them to come together peacefully.

I’ve found that in Nat’s adulthood, some of the wounds are still not fully healed, like my torn meniscus.

To the chagrin of many adults with autism, for parents, the term “wounds” is accurate. To many autistic adults, this feels like an insult – especially if they fully identify with autism. If they wear it as a badge of pride, a full aspect of their personality, you bet it’s an insult for the NT’s (neurotypically-wired people) to say that your child’s autism diagnosis wounded you deeply.

But we don’t mean it as an insult. It is a description of a state, of a feeling we have. It coexists, side-by-side with our love, admiration, hope, and all the other lovelier feelings. But if you are a person with a diagnosis that makes distinguishing grey areas and tolerating illogical anomalies, it will be hard for you to understand the many shaded band of crap feelings we NT parents harbor, that rest like steamy shit clouds over our rainbows of good feelings.

(Sorry about the extended metaphors and foul language but this is my blog, after all.)

That might be the difference between neurotypical parents and adult autistics. For it is a laceration to the parent to learn that your child is going to struggle terribly and that the world is not yet set up to accommodate him. This is the issue that has remained the same for me even in Nat’s adulthood because I watch him try to navigate the world and he is so ill-equipped, and so is the world. Something always interrupts his connecting words to himself. Whether typing or talking (so please don’t tell me to try typing. I do get him to type but it is still crazy hard for him to keep the waves of – whatever – from breaking his concentration.

Nat cannot even tell me he feels sick. He does not say, “I am hungry.” Finding words for him is like chasing bubbles; you might actually catch one on the eternal breeze but it will likely pop when you touch it.

I don’t even know if Nat knows that he’s different – very different from most people. But, knowing Nat, who listens to everything even though he appears to be in his own thoughts and language – he knows something about his difference. It could even be that he does his self-stim stuff to separate himself out further. Like he’s given up, mixed with a big bravado-like “fuck that noise,” to the rest of the neurotypical conversations around him.

I want to grab his brain and squeeze it between thumb and forefinger and shout, “Focus!” Which is a very ugly, ineffectual thing for a mom to do. It’s like the massage therapist who growls, “Relax,” when he’s working your knots. Shouting, “Focus!” at Nat is the tsunami that crashes over his concentration. That’s the real autism tsunami – the waves and waves of interrupts they encounter.

I want to stroke his brain in silence so that he stays with me, and in lying still, utterly relaxed, the words will come into focus like a highway sign as you get closer.

I want to find a way to get blood to flow, over his torn neuron connections, over my flaccid cartilage, and make it better.

With autism, there are threats that come from without, and threats that come from within. Number one external threat: cutting services. School systems. Adult services. Every budget season there are challenges we face on the government level, in the form of proposed cuts to services. This spring is no different; first we had to rally over the Governor’s proposed “9c” cut to Medicaid/Mass Health services in the form of Adult Family Care respite time for the caregivers. What in the world could they have saved financially speaking that would be worth denying 14 days vacation time for caregivers — people who work with those with very challenging disabilities and are responsible for their clients 24/7?

Soon after this proposal came the heinous Senate budget which cut, among other valuable services, Adult Day Program money for possibly 1,000 people who recently turned 22 (last hired, first fired I suppose). Other services to be cut: toileting and feeding assistance. So… let’s see. These people with intellectual disabilities with feeding and toileting issues will now have to — fend for themselves: Let them eat cake, or, uh, let them… hmm. Yeah. That’s what I thought.

Then there are threats from within. These are excruciating because they are directly about our child. Number one for me: what is Nat feeling? Is he okay? Latest thing: he is very quiet, slow, and still, like he is moving through water. He just stands there waiting for — what? And of course, no smiling in sight. On the other end, when he is not like this, he will suddenly switch to uncontrollable seemingly context-free laughter. Spitting laughter. So then we have to get him calm and more, well, serious, which then leads to — the still, quiet, somber Nat.

Where is the middle ground? Not just for my own exhausted heart. But for Nat. What is it like for him to exist this way, battered between so much up and down? How can I help him?

And by the way, when I ask that, it is rhetorical. I do not want any advice in the comments. Frankly, I hate other people’s advice. It so rarely fits our situation. It so often is something I’ve already tried. I honestly don’t believe anyone has the answers, and that is the way it has always been for Nat and us. We’re on our own and you are our supports. I only find it inside the autism community, but only from those with open arms and open minds.

Massachusetts families, advocates, and caregivers. Did you know that Mass Health is filing for a 9C cut, which in this case means WITHHOLDING 2 WEEKS RESPITE TIME FOR ADULT FAMILY CAREGIVERS???? This is unconscionable. Those that work with our guys need time off! Write to Mass Health if you can and tell them they must not do this. As Gary Blumenthal and the ADDP have told their constituents: PUSH BACK!! Protect our vital caregivers’ right to respite!

Note: Nat is not an AFC client but there but for the grace of DDS funding goes he!

Write to: masshealthpublicnotice@state.ma.us

Here’s my letter, just use it however you can.

Dear Mr. Tsai, et al.,

My son is 25 and has fairly severe autism. He is *not* an AFC user because he has had the “good luck” to be severe enough to warrant Priority One funding with the DDS. However, we had planned on using AFC in case we could not attain the Priority One. Since he’s been an adult, I have come to know others — younger families whose children are aging out of the school system — who will be applying for the AFC program. The AFC program is pretty much the only support for them, because DDS is strained and now the Autism Omnibus Bill has made it possible for *more* of those on the autism spectrum to apply for services. Yet, what are the chances that this newly eligible population will actually get anything, the way the DDS budget is?

So if families are lucky enough to get AFC, they can at least count on a small stipend for their work with their loved ones. They love their clients/disabled family members but the work is very very rough. I know this, from having my son live with me all the years prior to his residential move. Oh, how my heart broke to send him to live at his school. I still cry when I drop him off at his apartment with his caregiver. His caregiver is trustworthy and wonderful but he needs time off.

Don’t you get vacation time for your stressful jobs? Then how is it that you can file to suspend 14 days respite for AFC caregivers?? How can you possibly live with yourself doing that? What you need to do instead is work harder for the funds to support this respite. As people in charge of Health and Human Services, you owe it to your clients to advocate for them, not to reduce their lives.

You must do the right thing. Let the Legislature find the money somewhere else and do NOT take it from poor hard working caregivers!

Thank you,

Susan Senator

Can I say this? I hate the fact that I have to pay for people to be with Nat. Pay someone to live with him, pay someone to work next to him at the supermarket.

Can I also say this? I am so lucky that I can pay for people to be with Nat and that there are good people for this.

But, this whole thing makes me very sad. I think about when I was in therapy, and how it stung that I was not actually friends with my therapist, I was basically a customer. A client. She loved me, I’m sure. But she was working when she was talking to me. She had a life that I was not allowed into. There was an utter imbalance, where she knew all about me, and I knew almost nothing about her. When I would run into her in a store, it was so weird! There she was, herself, an older woman with a handbag buying stuff! It made me feel almost sorry for her. Or embarrassed? Why? The mask of the professional her was off at that moment and there was just the skin of her face hovering vulnerably in space.

So what is it like for Nat? The age old question: how much does he know about his life? And whatever he does know, how much of it bothers him?

Here goes, the horrible question: Do people with disabilities sometimes feel inferior because of what they cannot do, because they must depend on others? Oh, how Ableist of me to ask that, but I want to know, I want to hear about it.

Or is it just like it is for me, where you do come to accept that there are services you require that you must pay for. Like seeing my doctor. Hiring a plumber. I can feel stupid and incompetent if I need someone to look at a hurt knee and tell me why it hurts, but I don’t. We accept that there are professionals in our lives to do for us what we cannot.

So — is that the reality Nat knows?

Or does he wish that instead of a paid live-in caregiver, he had just a roommate, a friend?

It is so painful but I have to ask. And of course there are no answers. Of course. That is the real problem of loving someone who has a profound disability. There is indeed mystery and you are constantly reminded of how terribly human (flawed, limited) you are that you cannot give this beautiful person exactly the life he should have.

“Should?” What is the truth here?

I burst into tears today as I was riding my bike — not because of the ride but because of where my mind suddenly went. I was thinking about my Uncle Alby who had just died, and then, of course, of my mom, his little sister. I call her that because around him she really became a younger version of herself, naive, innocent, waiting in joyful anticipation of what Alby would say next.

It was thinking of Mom that brought on the tears. Mom, and then Dad. The two of them have been hit very hard by a string of peer and family deaths lately. All of these people died of old age, but they were not that much older than my parents. I think Mom especially is feeling her own mortality very deeply lately because of this. Her small copper face seems a bit more closed in on itself, her eyes seem lighter brown than they used to be, and when she was here a few days ago they seemed to be looking for something. She hugged me quite a bit that day she was here to say goodbye to Alby — and I hope that for those moments she’d found a little of what she was needing. I could feel the full force of her vulnerability, lying against me, yet also, the way her arms bent around me there was also the age-old care of the mother for her child. Mom is complicated, young and old at the same time, brilliant and naive, nakedly open and yet mysterious. And if you happen to be one of the lucky ones she loves, you will always always feel that.

Dad is likely feeling the same kind of sorrowful things, but he shows it differently. He’s all silver and gold these days, his hair gleaming gray-white, his skin burnished tan from always being outdoors. He’s like a benevolent floaty cloud in a summer sky, watching over you, playfully hiding now and then with the sun. A life of hard work, muscular movement and exercise, and constant thought have polished him down to his very essence: joy.

I don’t mean for this to sound like a eulogy. But it occurred to me today that I need to say these things while they are alive.

I did not have a perfect childhood. But unlike many people, I had parents who desperately wanted and tried to be perfect. And for years and years I believed they were, even though experience told me they were not. When I finally realized they were not perfect people, and that they had actually made mistakes parenting me, I was so angry. And this was later in life, I’m ashamed to say.

Now what I know is that goodness in a person is not about perfect, it’s about being human. And they are so very human. Yet their drive to be perfect for me and my sister Laura shaped me into the same kind of person. Someone who does not question trying really really hard for those you love, someone who wants to make loved ones and others, too, really really happy. In being that way, they made me a good person. And they gave me a wonderful childhood. Not perfect, but that’s okay. Because it was wonderful. With some awful times, but still — amazing. Should I name these things? Give you a picture of what I mean?

First thing that comes to mind is a sense of wonder. The four camping trips out West, returning each time to a favorite campsite in Rocky Mountain National Park. The North Rim of the Grand Canyon “because it’s less crowded.” The smell of the wilderness that Mom wished she could “bottle.” Driving through the desert with water strapped to our car “just in case.” So much adventure. These trips gave me the feeling that I could go anywhere, do anything, that the world had endless places to discover. That you could spend hours and hours with people in one car and only get closer to them. I need to be honest, of course, and say that there were times when I’d be so angry or hurt by them that my throat would choke with rage and sorrow. But I understand it all now, and I forgive them. This is so important. To forgive and let go so you can love even better.

Second thing they gave me: humor. My Mom probably learned from her father and then Alby all about laughter and she found my father early in life — age 13, married him at 18 — because he continued the tradition of making her laugh. You have never seen high cheekbones until you’ve seen Mom laugh. Diamond bright teeth. And Dad is so funny, I don’t know where to begin. I have wanted to write about his humor for years but I just can’t yet. It’s so much a part of my own wiring that I can’t untangle it. I hope to someday. For now I will say that I hear his jokes without him even being there. My sister Laura and I are also funny because of Dad, and we both chose husbands who make us laugh, accordingly.

Third thing: activism. My parents are dedicated to helping people. They are teachers by profession. But they help so many people other than students. They have changed people’s lives just by their own honesty and hard work and no-nonsense attitude. I was miserable in my first year of college. “So transfer,” Mom said. And just like that, I learned that I never have to accept a miserable situation. And I don’t. Even if that means that I’m confronting her for something she said! And Dad, asking me one evening if a certain boyfriend was “making me happy.” And the answer, of course, was No. But Dad made me face it, and end that destructive relationship.

Fourth thing: duty. My parents always try to do the right thing. You must take care of your loved ones and friends. You must tell someone when they are not being wise or kind. Stand up for others. Stand up for yourself. Sometimes it drives me crazy, I feel like they sometimes put off happy things because there’s Something They Must Do. But that’s in me, too. I do the same thing. Everyone around them relies on them, on me.

Fifth thing: health. My parents tend to overdo their dedication to their physical fitness, but that is who they are. And they are very strong because of it. For their age, and for any age. I still do not want to try to race my Dad on a bike. Certainly not in running. Mom walks sometimes 10 miles in a day, listening to NPR or books. Always learning. Dad listens to nothing but his own thoughts and he simply becomes a part of the road he is running or riding on, his breath is the air around him,. Both of their different ways make perfect sense for who Mom and Dad are.

Sixth thing: to be learned. The constantly admonished me to read, know the classics, be conversant in current events, philosophy, literature, ethics. Both of them are always reading more than one book. Always. They feel what they read, they think think think and then they tell you all about it. And now I’m the same.

I grew up in love with Mom and Dad. They were larger than life, they were my Gods. Then they fell from grace, simply because I learned they were just people. I had to learn that no one is larger than life, no one is a God, but that this is okay, that this is right. I had to also learn that I was okay. This took so long. So much to learn again and again, as an adult, so much gray confusion, black struggle, blood red anger.

Only to find that the beautiful elements of diamond, copper, silver, and gold outlast everything else.